There’s a lot written on the web and elsewhere about the magical powers of lime, but there still seems to be a lot of confusion amongst bricklayers who (like me) were brought up in the Cement Age, when lime was thought to be a thing of the past, like slide rules and smallpox.

SCENARIO:

A brick wall, built before 1920 and looking a bit tatty. Some of it might have already been re-pointed, using a cement mortar – this brittle grey hard stuff sticks out like a sore thumb and already the surrounding bricks are starting to spall and crack, and damp is penetrating to the inside of the building. What is going on?

Basically, Portland cement is chemically different from lime and its strength, rapid hardening and resistance to moisture can be damaging to traditional masonry.

Using traditional lime mortar takes time, and this is expensive – it can be tempting to add “a bit of cement” to speed things up, but this will shorten the life of the wall and do more harm than good – don’t do it!

Often, there is confusion as to what lime mortar actually is – sometimes a cement mix with a greater than normal proportion of bagged lime is called a lime mortar, when in fact it is not. In this case, the lime is added as a plasticiser to improve the workability and adhesion of the mix but the presence of cement makes it a cement mortar!

Bagged lime is similar to slaked lime, being Calcium Hydroxide, but the addition of water to quicklime (Calcium Oxide) is carefully controlled to produce a dry powder instead of a putty. It is possible to make lime putty ready for use from bagged lime, but the process of maturation over several weeks improves the particle structure of the lime and its performance in use. Hence, nowadays it is generally more convenient to buy ready-matured lime putty in plastic tubs.

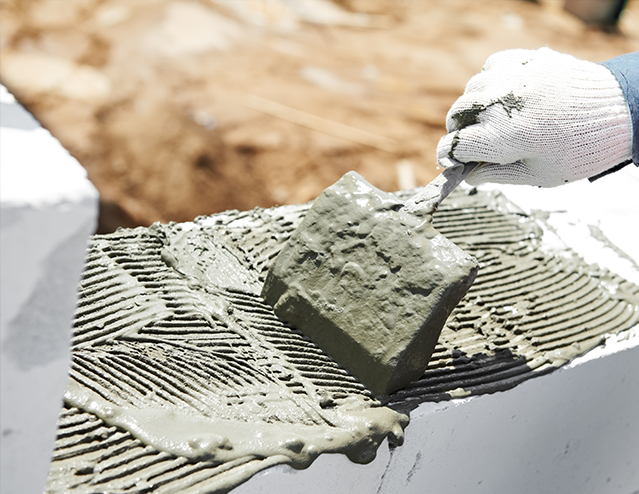

Traditional lime mortar is simply slaked lime and sharp sand (no cement!); to make a good match between the original work and the repairs it is important to match the colour and texture of the locally-quarried material.

Traces of clay in the lime may add silica and alumina to make it weakly or feebly hydraulic – this is defined as the ability to set under water and is produced by a separate chemical reaction to the usual absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Natural hydraulic lime (NHL) is quarried from deposits (often in France) where the impurities in the limestone give the appropriate blend of strength and setting time. This is graded from NHL2 to NHL7; the weaker grades being more flexible and appropriate for re-pointing and rendering and the stronger grades used for civil engineering work such as the great harbours, locks and bridges of the 18th and 19th centuries that are still in use today.

NHL can be used, with caution, for repair work where the circumstances allow a strict authenticity to be exchanged for a reduction in setting time. However, for most bedding and pointing repairs, the mix must not be too strong. In all cases, the mortar must be weaker than the masonry units (bricks, blocks or stone) that the wall is made from. This may mean that when building a cavity wall with a block inner leaf and brick outer leaf, a different mix is required for each material.

An analogy is that the mortar should act a bit like cartilage in a skeleton; it provides a cushion to distribute stress evenly across the masonry unit and allows for a degree of movement. Unlike cement mortar (and my knees), lime has the ability to “self-heal” by forming new bonds between particles.

CONCLUSION:

For pre-1920 masonry; cement is naughty. Even for modern brickwork, mortar should not be over-strong and the addition of lime improves workability and tolerance to movement. Maybe I should come up with a nice mnemonic, but to rhyme with lime is fine, not so easy with OPC!